Since we arrived the previous evening to Manassas National Battlefield Park (Part 1), we decided to take the auto tour the following day. Here are some of the auto stops that we visited.

Once the scene of bloody battle, the Brawner Farm sits today in a quiet corner of Manassas Battlefield.

*Clicking on a photo will give you a closer look!

“My command was advanced…until it reached a commanding position near Brawner’s house. By this time, it was sunset; but as the [Union] column appeared to be moving by, with its flank exposed, I determined to attack at once.” – Confederate General Thomas J. Jackson, 1862

The Second Battle of Manassas had begun.

Outnumbered and exposed, the Union line held its ground, returning fire with discipline and great effect. The fight at Brawner’s Farm ended in stalemate leaving General Thomas J. Jackson frustrated by his troop’s inability to break the Union line.

John C. Brawner’s structure sustained considerable battle damage on August 28, 1862, and the Brawner family abandoned the farm soon after.

From Battery Heights, Confederate artillery repulsed Union infantry maneuvering over the open fields to the northeast near Brawner Farm, hastening their retreat.

As with the monument on Henry Hill, the Groveton Monument was constructed by Union soldiers and dedicated June 11, 1865. The monument honors the Federal dead of the Second Battle of Manassas. Souvenir hunters later stripped the monument of the artillery shells that originally adorned it.

“The Rebel infantry poured in their volleys, and we were scarcely a dozen feet from the muzzles of their muskets. Oh, it was terrible! For twenty minutes the shattered regiments held the slope swept by a hurricane of death, and each minute seemed like twenty hours long. For twenty minutes the bullets hummed like swarming bees, and then those yet alive and able to do so received orders to fall back. We who fell – the dead, dying, and the disabled – held the field.” – Corporal John S. Slater 13th New York Infantry Army of the Potomac Second Battle of Manassas

In Memory of the Patriots who Fell at Groveton Aug. 28th, 29th, & 30th.

Constructed prior to 1850, early owners established a tavern at Stone House, and served weary travelers on the Warrenton Turnpike. By 1860 wagon traffic had declined.

Major General John Pope made his headquarters on Buck Hill, directly behind Stone House. The house sheltered the wounded as a Union field hospital during both battles.

“The rattle of musket balls against the walls of the building was almost incessant.” – Unknown Soldier

Operating under a flag of truce, Federal surgeons tended to the wounded while the victorious Confederates used the house as a parole station for prisoners of war.

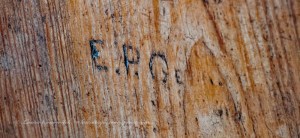

Two soldiers carved their names in an upstairs room.

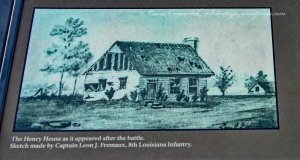

The Lucinda Dogan House small frame house stands as the only surviving original structure of the crossroads village of Groveton. Widow Lucinda Dogan and her five young children moved here shortly after their residence, “Peach Grove”, burned in 1860. The family joined two smaller outbuildings to create the present dwelling.

Major General James Longstreet dined at Dogan House.

The house was repeatedly caught in the crossfire of opposing Union and Confederate armies during the Second Battle of Manassas. Numerous bullets and shell fragments scarred the structure. Years later, the family sought compensation for property damage during the war. The government denied the claim.

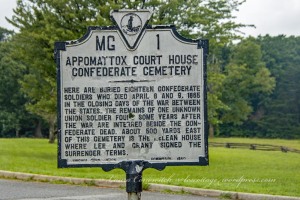

After the fighting at Manassas, burial details dug shallow graves where soldiers had fallen. Crude wooden headboards sometimes noted the soldier’s name and regiment. Many went to their graves anonymously.

The Bull Run and Groveton Ladies Memorial Association, established in 1867, launched a campaign to recover Confederate dead from the battlefield. The organization established the Confederate Cemetery on a knoll on the widow Lucinda Dogan’s land. They orchestrated the re-internment of an estimated 500 soldiers in trench graves. Few could be identified and only two graves have individual headstones.

Many of the Union dead were reburied at Arlington National Cemetery.

A brief, futile stand on Chinn Ridge, near Groveton, by the 5th, the 10th New York Regiments, and the 14th Brooklyn ended in slaughter. In five minutes, the 5th New York lost 123 men – the greatest loss of life in any Union single infantry regiment in any battle of the Civil War. One veteran compared it to “the very vortex of Hell”.

General James Longstreet’s wing of the army, upwards of 28,000 troops, pushed east towards Henry Hill. If Confederates occupied that plateau, the same ground on which the First Battle of Manassas had culminated the previous summer, they could cut off the Federals line of retreat and possibly annihilate the Union Army.

Stretched along Chinn Ridge, a handful of Union brigades desperately struggled to delay Longstreet’s counterattack upon Major General John Pope’s vulnerable left flank long enough for Pope to form a rearguard on Henry Hill. However, the overwhelming numbers of Confederates drove them back along the ridge.

The stone foundation is all that remains of the house of Benjamin Chinn. A trail leads to the boulder marker for Colonel Fletcher Webster, eldest son of the famous orator and stateman, Senator Daniel Webster, killed leading the 12th Massachusetts Infantry into battle.

“If a fight comes off, it will be today or tomorrow and will be a most dreadful and decisive one. This may be my last letter, dear love, for I shall not spare myself…” – Colonel Fletcher Webster, in a letter to his wife, written on the morning of his death.

Originally constructed in 1825, the Stone Bridge carried the Warrenton Turnpike across Bull Run.

Prior to abandoning the Manassas area, the Confederate troops blew up the original bridge in March 1862. The current structure dates to 1884.

Under cover of darkness, the defeated Union army withdrew across Bull Run in this vicinity toward Centreville and the Washington defenses beyond. The troops crossed Bull Run on a makeshift, constructed several months earlier by Union engineers using the remaining bridge abutments.

After the last soldier filed across the stream, the replacement bridge was destroyed by the Union rearguard on day 3, August 30, 1862.

For the Union army, the Second Manassas campaign ended in another defeat. President Lincoln relieved Major General John Pope of command and dissolved the Army of Virginia, reassigning the troops to the Army of the Potomac.

More than 23,000 Americans were casualties at the Battle of Second Manassas. Nearly 3,300 soldiers died. The dead of both armies were buried on the battlefield in makeshift graves. Not until the end of the Civil War, nearly three years later, would most of the dead receive proper burials. Some of the dead may still remain buried in unmarked graves on the battlefield.

Manassas National Battlefield Park Part 1

See the world around you!