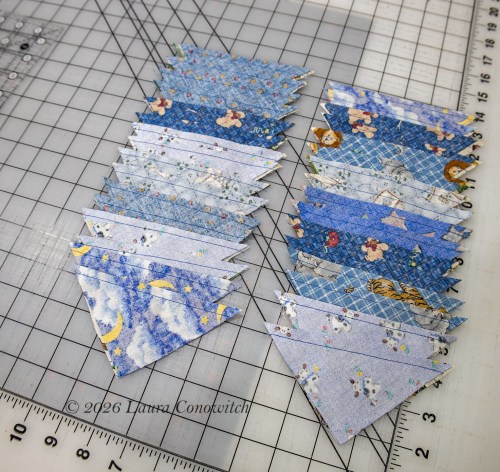

I settled on a star layout for the half-square triangles made from the 1990’s charm squares.

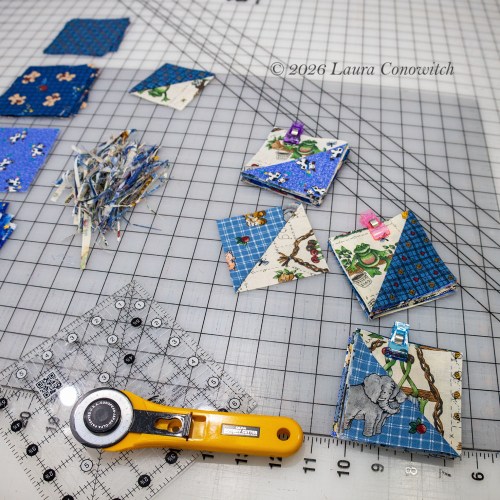

I don’t have a large wall, or the floor space, to lay out blocks, but we all make do with what we do have.

The stars are set with squares and this was simple to stitch up.

I had enough parts left over (including the odd sized half-square that I threw in the parts department and retrieved) to make two more star blocks for the back.

All marked and pinned.

I have chosen to do easy cross-hatching with a walking foot.

Nothing fancy to see here.

Have fun and carry on!

Previous Post: