During the heavy fighting late in the afternoon of July 1, 1863, Seminary Ridge became the final defensive position of the Union’s First Army Corps west of Gettysburg. Twenty-one cannons and thousands of battle-weary men crowned the heights with the aim of repelling Confederate forces ascending the ridge.

Schmucker Hall (Old Dorm), now known as the Seminary Ridge Museum is a must see stop if you are going to visit Gettysburg National Military Park.

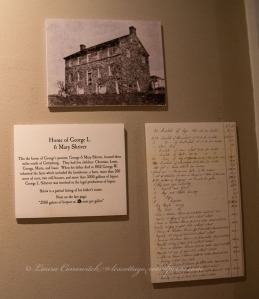

The Museum houses displays of many different aspects of the battle, the seminary, the town, and the civil war, and the struggle among faith groups over slavery, as well as offering tours of the cupola.

The Lutheran Theological Seminary opened with 11 students on September 5, 1826, at the 1810 Gettysburg Academy building.

*Clicking on a photo will give you a closer look!

Old Dorm was used during the Gettysburg Campaign as an observatory and the surrounding area was used by both the Union artillery (morning of July 1st, 1863) and Confederate artillery (captured in late afternoon). Over 600 wounded Union and Confederate soldiers were treated inside and on the grounds.

“On every side the passion, rage and frenzy of fearless men or reckless boys devoted to slaughter or doomed to death! The same sun that a day before had been shining to cure the wheat-sheaves of the harvest of peace, now glared to pierce the gray pall of battle’s powder smoke or to bloat the corpses of battle’s victims.”

—Augustus Buell, “The Cannoneer” (1890)

For shattered bones of arms and legs, amputation was the most successful treatment available. Piles of amputated limbs accumulated on the floor or outside the windows of rooms used for surgery. At the Seminary, ten-year-old Hugh Ziegler helped the medical staff by carrying away severed arms and legs.

“It was a ghastly sight to see some of the men lying in pools of blood on the bare floor. Night and days were alike in spent in trying to alleviate the suffering of the wounded and dying,” wrote Lydia Ziegler (a teenager living with her family on the first floor.

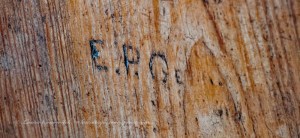

“Major, Tell my father I died with my face to the enemy.” – I E Avery (written in a note)

On July 1st, 1863, as the men of the 151st Pennsylvania Volunteers made a final stand on the west side of the Seminary, Lieutenant Colonel George F. McFarland was struck by bullets in both legs. Private Lyman Wilson dragged his commander through the north door of the Seminary as Confederates rushed through the south end.

His wife, Addie, arrived July 10th with their young children, and stayed until the end of August. From September 7th to the 16th, 1863, McFarland was the only patient remaining at the Seminary. He was confined to bed for another 7 months. He resumed teaching and converted his school to an orphanage for the children of soldiers.

In 1800, there were 114 slaves in Adams County, Pennsylvania: most owned by farmers. By 1830, the number dropped to 45, and by 1840, there were just 2.

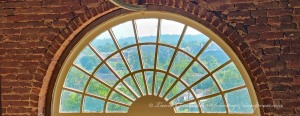

On June 30, 1863, Brigadier General John Buford climbed to the cupola of the Lutheran Seminary Building, where he saw the campfires of thousands of Confederate soldiers burning to the west.

Predicting a clash was imminent, this view helped him lay out his lines of defense to protect Gettysburg’s pivotal road network.

The next morning, as the largest battle in the Western Hemisphere erupted, Buford again ascended to the Cupola to watch for vital Federal reinforcements.

There is much more to Seminary Ridge than the museum. The following is a small sample of what you see when you take a walk (or a drive):

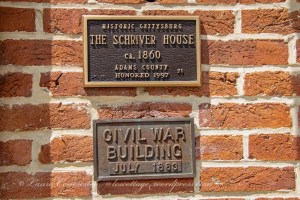

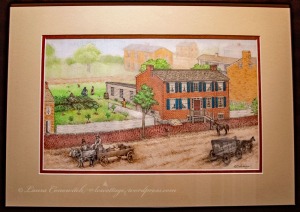

Gettysburg Shriver House Museum

See the world around you!