Grand Village of the Natchez Indians, Mississippi

After staying in a hotel in Baton Rouge, as opposed to car camping, we headed towards Natchez, Mississippi.

We passed under the Tensas River Bridge, Louisiana, a vertical lift drawbridge built in 1971. It is no longer in operation for river traffic but, obviously, still used by vehicles.

I thought it was cool!

*Clicking on a photo will give you a closer look!

We didn’t stop to look around the bridge area, but we did make an unplanned stop when we saw a sign for the Grand Village of the Natchez Indians.

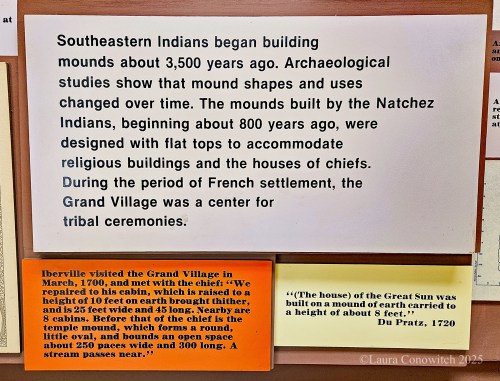

The Grand Village is a 128-acre site featuring three prehistoric Native American mounds, a reconstructed Natchez Indian house, a museum with artifacts and a film to see, a gift shop, and a nature trail. There is an annual Natchez Powwow, featuring traditional Native American singing and dancing, foods, crafts and more. Admission is free.

The Natchez Indians were successful farmers, growing corn, beans, and squash. They also hunted, fished, gathered wild plant foods, made baskets and pottery.

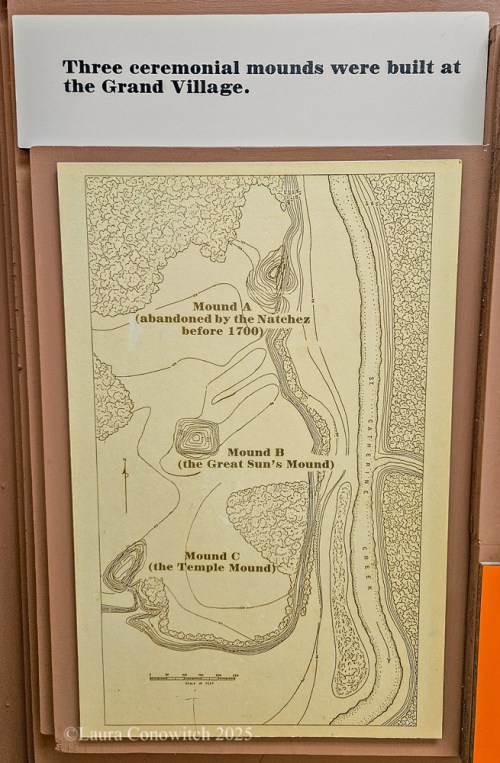

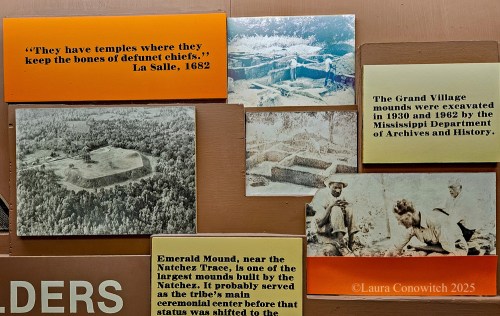

The Natchez Indians and their ancestors inhabited what is now southwest Mississippi ca. AD 700-1730. According to historical and archaeological evidence, the Grand Village was their main ceremonial center between 1682 and 1730. French explorers, priests, and journalists described the ceremonial mounds built by the Natchez on the banks of St. Catherine Creek. Later archaeological investigations produced additional evidence that the site was the place that the French called “the Grand Village of the Natchez.”

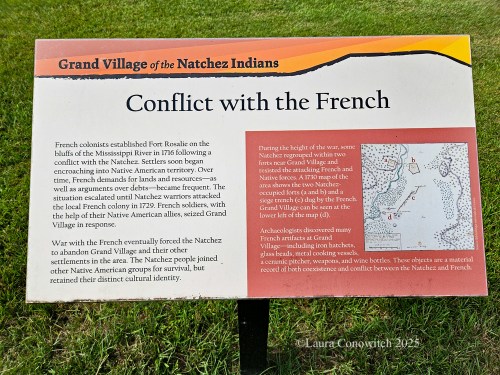

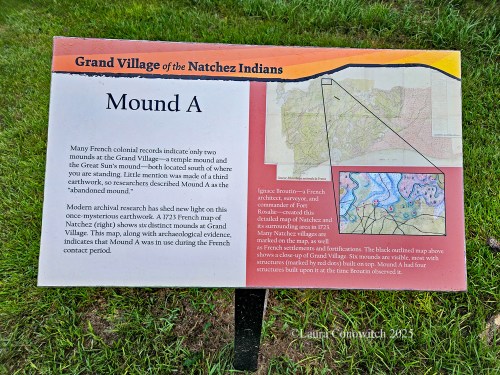

French settlers began to explore the region and establish settlements that gradually encroached on Natchez territory. Though relations were peaceful at first, the French colonists strained the resources the Natchez relied on for survival. Several episodes of violence in 1716 and 1723 created tension, although the Natchez made land concessions to the French. In 1729, a pro-English element within the nation led the Natchez to attack the French colonial plantations and military garrison at Fort Rosalie.

In 1731, after several wars with the French, the Natchez were defeated. Most of the captured survivors were shipped to Saint-Domingue and sold into slavery; others took refuge with other tribes, such as the Muskogean Chickasaw and Creek, and the Iroquoian-speaking Cherokee.

Mound A, or the Abandoned Mound, has been only partially excavated. Research indicates that as many as four structures were on top of it in the 1700s. After three major archaeological excavations at the Grand Village by the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, no further digging investigations are planned for the site. The unexcavated areas of the site will be preserved intact, representing a sort of “time capsule” from the Natchez Indians’ past.

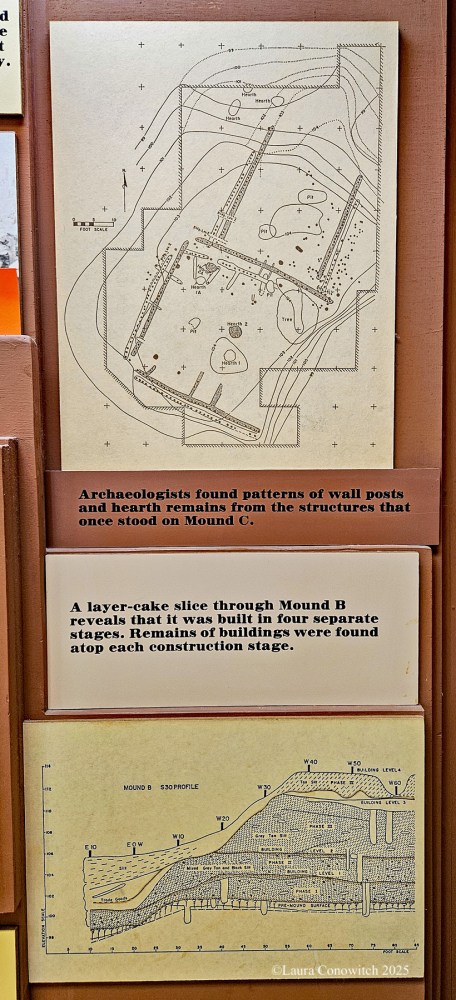

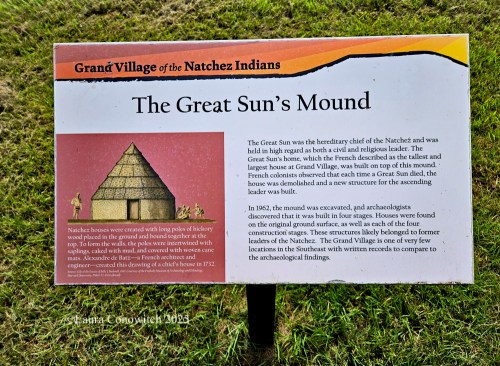

Two of the mounds, the Great Sun’s Mound, and the Temple Mound, have been excavated and rebuilt to their original sizes and shapes.

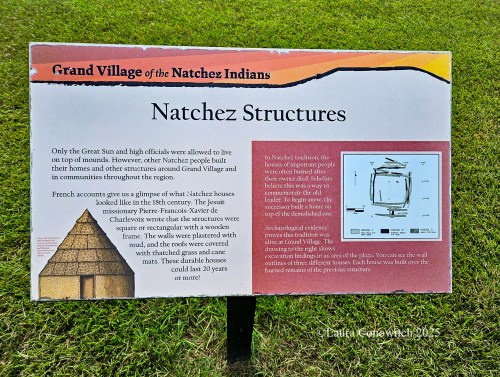

The Great Sun’s home, described by the French as the tallest and largest house at Grand Village, was on top of this mound. Each time a Great Sun died, the house was destroyed and a new house built for the new Great Sun.

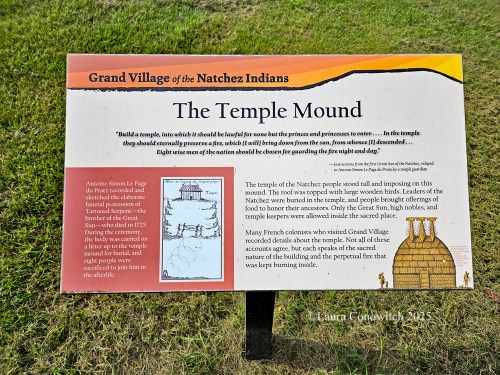

A religious structure once stood atop the Temple Mound and housed bones of previous Suns. A sacred perpetual fire was kept in the Temple’s inner sanctum, symbolic of the sun, from which the royal family had descended.

The Natchez performed ritual human sacrifice upon the death of a Sun. When a male Sun died, his wives were expected to accompany him by performing ritual suicide. Great honor was associated with such sacrifice, and sometimes many Natchez chose to follow a Sun into death. For example, at the death of the Tattooed Serpent in 1725, two of his wives, one of his sisters (nicknamed La Glorieuse by the French), his first warrior, his doctor, his head servant and the servant’s wife, his nurse, and a craftsman of war clubs, all chose to die with him.

Mothers sometimes sacrificed infants in such ceremonies, an act which conferred honor and special status to the mother. Relatives of adults who chose ritual suicide were likewise honored and rose in status. The practice of ritual suicide and infanticide upon the death of a chief existed among other Native Americans living along the lower Mississippi River, such as the Taensa.

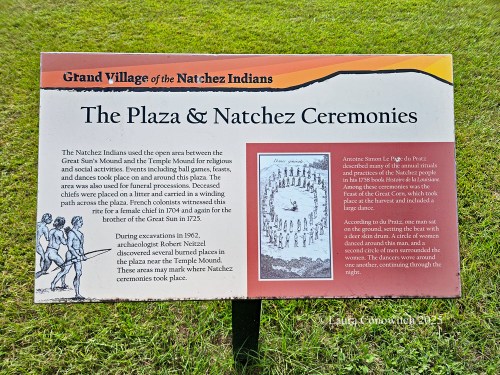

The open area, or plaza, between the mounds was used for religious, social, and funeral activities.

See the world around you!

More Travel Posts: