Andersonville National Historic Site, Georgia-Part 2

In my last post, I shared some of the exhibits you can find in the National Prisoner of War Museum at the Andersonville National Historic Site.

I will share some of the grounds of Andersonville Prison in this post. However, if you haven’t seen my last post, I strongly suggest reading it first, as much of what occurred here is shared there.

The Memorial Courtyard at the rear of the museum displays a meandering stream recalling the water themes common to many POW experiences, and a major brick and bronze sculpture.

It is meant to be a place of contemplation.

*Clicking on a photo will give you a closer look!

Behind the Memorial Courtyard are the grounds of Andersonville Prison.

You can get a brochure from the visitor’s center. I suggest watching the films, and viewing the exhibits in the center before walking the grounds. There are signs everywhere, but you will feel more oriented if you visit the museum first.

Replicas of tents that prisoners used for shelter. Many prisoners had no shelter, or even proper clothing, to shield them from the elements.

Successful escape from Andersonville was virtually impossible, and it was much rarer than what has often been portrayed. Even most of those who managed to successfully escape from Andersonville did so between the Fall of 1864 through the Spring of 1865, when the prison and its security systems were breaking down as the war ended.

Escape from Camp Sumter (Andersonville) had an extremely high rate of failure. For a Union prisoner to make a successful attempt for freedom from the prison compound, he had to make it past stockade walls, guards, artillery surrounding the stockade, local militia, citizen mobs, and patrols with tracking hounds. Patrols for Confederate deserters and escaped slaves often caught escaped prisoners, sending dozens of men back to the stockade.

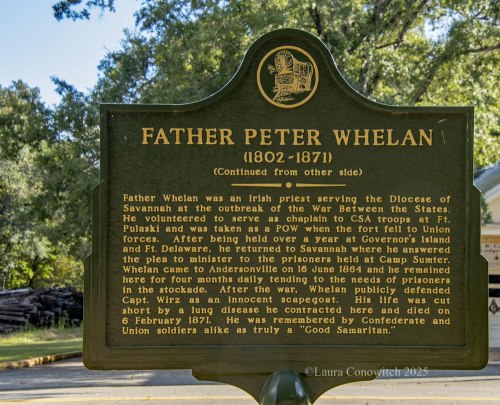

When the prisoners returned home and wrote their memoirs, Father Whelan and his work was often recalled. Some mentioned that he had brought clothing, food, and money from Savannah. One added, “without a doubt he was the means of saving hundred of lives.” Another described Whelan’s ministering to the sick: “All creeds, color and nationalities were alike to him…He was indeed the Good Samaritan.” A sergeant, John Vaughter, in his memoirs remarked that, “of all the ministers in Georgia accessible to Andersonville, only one could hear this sentence, ‘I was sick and in prison and you visited me,’ and that one is a Catholic.”

After Father Whelan’s departure in late September, he borrowed $16,000 in Confederate money, the equivalent of $400 in gold, and purchased ten thousand pounds of wheat flour. He had it baked into bread and distributed at the prison hospital at Andersonville. It was enough bread to provide for the men for several months.

Clara Barton, the “Angel of the Battlefield”, nurse, humanitarian, founder and first president of the American Red Cross, spent the summer of 1865 helping find, identify, and properly bury 13,000 individuals who died in Andersonville prison camp.

In Commemoration of the Untiring Devotion of

Clara Barton

She organized and administered efficient measures for the relief of our soldiers in the field, and aided in the great work of preserving the names of more than twelve thousand of the brave men who died here.

Erected 1915 by Woman’s Relief Corps, Auxiliary to the Grand Army of the Republic.

“Let Us Have Peace“

“Death Before Dishonor”

There are other monuments at Andersonville than the few that I have shared in this post.

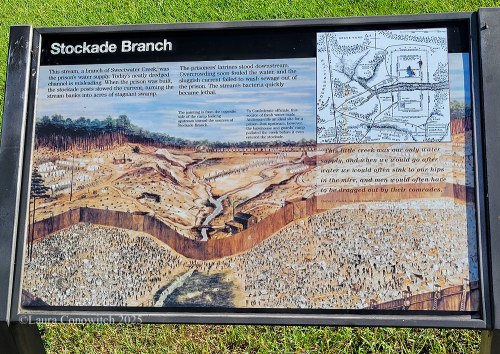

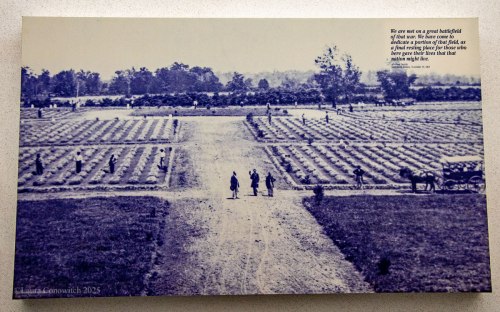

The prisoners’ water source, the Stockade Branch, a branch of Sweetwater Creek, was contaminated with human waste and oils from the Confederate guards’ camp before it even got to the prisoners.

“A spring of purest crystal shot up into the air in a column and, falling in a fanlike spray, went babbling down the grade into the noxious brook. Looking across the dead-line, we beheld with wondering eyes and grateful hearts the fountain spring.” – John L. Maile, 8th Michigan Infantry August 15, 1864.

The miracle stream of water was named Providence Spring.

Anderson was named for John Anderson, a director of the South Western Railroad in 1853 when it was extended from Oglethorpe to Americus. It was known as Anderson Station until the US post office was established in November 1855. The government changed the name of the station from “Anderson” to “Andersonville” in order to avoid confusion with the post office in Anderson, South Carolina.

The town also served as a supply depot during the war period. It included a post office, a depot, a blacksmith shop and stable, a couple of general stores, two saloons, a school, a Methodist church, and about a dozen houses. Ben Dykes, who owned the land on which the prison was built, was both depot agent and postmaster.

“Then came the captives, weary, worn and hungry from prolonged travel cooped up like beasts in freight cars. Down from the depot they marched amid the jeers and taunts of a gaping crowd. The gate opened. The stockade swallowed them.” – Lessel Long, 13th Indiana Infantry, February 21, 1864

“Once inside…men exclaimed: ‘Is this hell?’ Verily, the great mass of gaunt, unnatural-looking beings, soot-begrimed, and clad in filthy tatters, that we saw stalking about inside this pen looked, indeed, as if they might belong to a world of lost spirits.”

W.B. Smith, 14th Illinois Infantry

October 9, 1864.

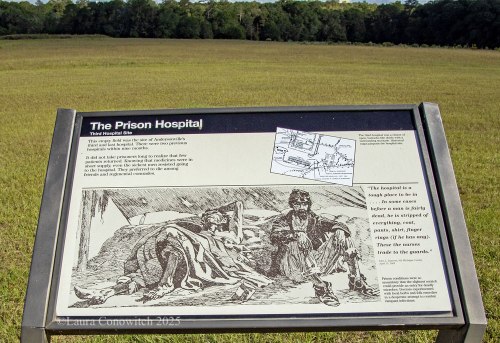

“The hospital is a tough place to be in….In some cases before a man is fairly dead, he is stripped of everything, coat, pants, shirt, finger rings (if he has any). These nurses trade to the guards.”

John L. Ransom, 9th Michigan Cavalry

April 15, 1864

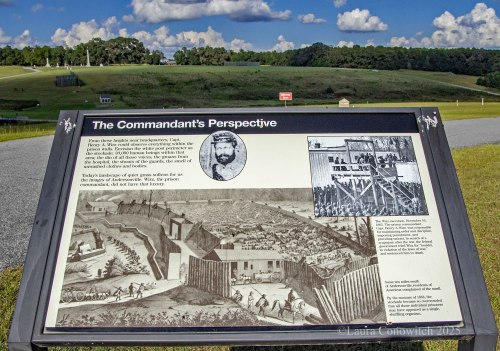

From these heights near headquarters, Capt. Henry A. Wirz could observe everything within the prison walls. Envision the white post perimeters as the stockade; 30,000 human beings within that area; the din of all those voices, the groans from the hospital, the shouts of the guards, the smell of unwashed clothes and bodies.

The guards—mostly old men and young boys from the Georgia Reserve Corps—were reluctant witnesses to the misery at Andersonville. More seasoned troops were sent to stop Sherman’s drive toward Atlanta.

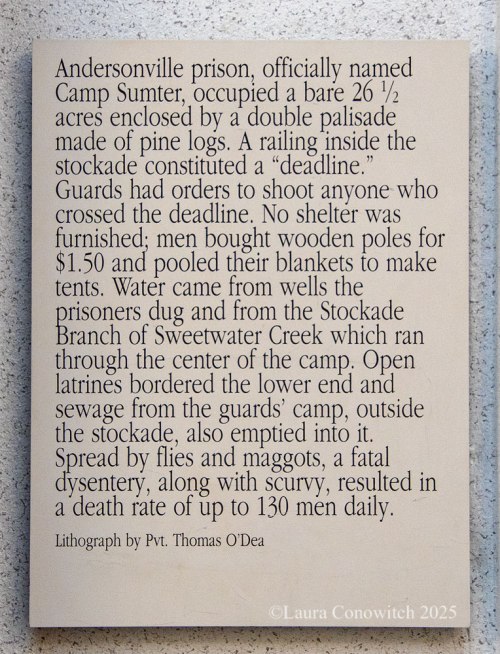

Forms of punishment at Andersonville included death, “bucking and gagging,” hanging up by the thumbs, and physical punishment like whipping for offenses such as stealing. The prison’s harsh conditions and severe overcrowding also acted as a de facto punishment, leading to widespread death from disease and malnutrition. Additionally, guards had orders to shoot any prisoner who crossed the “dead line” or spoke to a sentinel.

Firsthand Account of Private Prescott Tracy, Civil War POW

See the world around you!

More Travel Posts: